National registry launched to transform care for people at risk of type 1 diabetes

A first-of-its-kind UK registry for children and adults who are at risk of type 1 diabetes has been launched at the University of Oxford.

With more than £600,000 of funding from Diabetes UK, the UK Islet Autoantibody Registry (https://www.ukiab.org) aims to transform how people in the earliest stages of type 1 diabetes are monitored and supported, and act as a gateway to ground-breaking clinical trials and treatments.

The national registry will follow children and adults who have tested positive for type 1 diabetes autoantibodies through research studies or in clinical care.

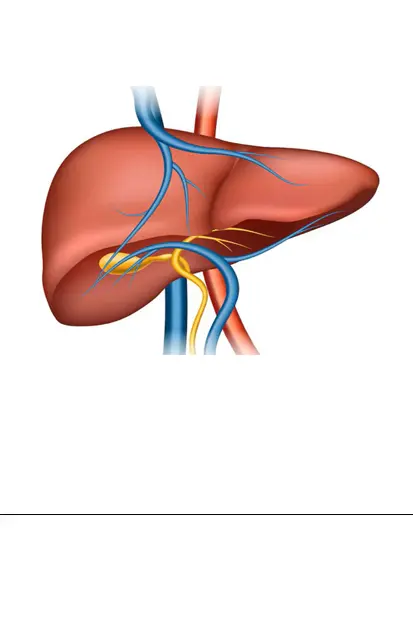

Type 1 diabetes is a serious, lifelong autoimmune condition that affects up to 400,000 people in the UK. It occurs when the immune system mistakenly attacks insulin-producing cells in the pancreas, preventing the body from making insulin and causing dangerously high blood sugar levels.

When the immune system attacks, it produces proteins called autoantibodies, which can be detected with a simple blood test. Autoantibodies can appear months or years before symptoms of type 1 diabetes develop and an individual receives a diagnosis. People with two or more autoantibodies are almost certain to develop type 1 diabetes in their lifetime.

Unfortunately, many individuals who test positive for type 1 diabetes antibodies have not been studied over the longer term. This means researchers and clinicians have limited understanding of how best to support those living with the knowledge they are very likely to develop type 1 diabetes. They are also limited in their ability to tell people about new trials or treatments that could delay the onset of type 1 diabetes.

Last month, teplizumab became the first ever immunotherapy for type 1 diabetes licensed for use in the UK, when it was approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). In people with two or more autoantibodies, teplizumab, also known as Tzield, has been shown to slow the progression of type 1 diabetes, giving them extra years before the condition fully develops and insulin treatment is needed.

The aims of the registry are to:

- Tell people about new treatments and opportunities to take part in research to prevent or delay type 1 diabetes

- Monitor people with autoantibodies for the onset of high blood sugar levels so they can start insulin treatment as soon as possible. This will help prevent them being diagnosed in diabetic ketoacidosis – a life-threatening condition requiring hospital admission – which currently affects more than one-third of children at diagnosis.

- Develop resources to support people living with the knowledge they have type 1 diabetes autoantibodies, to reduce anxiety and worry

- Provide guidance for the NHS on how best to care for and support people who have type 1 diabetes autoantibodies

- Collect data to better understand how type 1 diabetes progresses through its early, pre-symptomatic stages and whether being at risk causes people to attend their GP or A&E more often

Dr Rachel Besser, a paediatric diabetes consultant at Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and researcher at the University of Oxford’s Centre for Human Genetics, is leading the project. Her work is supported by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC).

She explained: “This registry is a first for the UK and brings together children and adults who are at risk of type 1 diabetes. It is an important step towards a better understanding of the care and support people at high risk of this condition require, allowing us to offer them a ‘softer landing’ into life with the condition, as well as opportunities to take part in studies testing drugs to delay type 1 diabetes occurring.

Tracy Savory leads the registry’s Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group. She has a daughter who was identified through research as having type 1 diabetes antibodies, as well as having a son with type 1 diabetes.

She said: “I have a dual perspective on this; having a child who was seriously ill at diagnosis of type 1 diabetes, I really understand the importance of catching it early. But I’m also aware that if you have a child who is autoantibody positive who isn’t involved in research, there is a lack of follow-up.

“When you are initially told your child is autoantibody positive, you are processing that information and maybe not taking everything on board about what the implications are. Having a trusted, single point of reference to go to when you need to revisit that information, in your own time, will be a vital resource.

“The registry is developing pathways to support people and sharing this information with primary care. There is also the opportunity to find out about any trials that could possibly help, rather than having to trawl the internet ourselves.

“For my daughter, who doesn't know anybody else in the same position as her, it will be a comfort to find out about other people in a similar situation and hear their stories, just to understand more about what it means to be autoantibody positive. With the registry, it feels like she will be more supported in a range of ways.”

Dr Lucy Chambers, Head of Research Impact and Communications at Diabetes UK, said: “There’s a crucial window - months or even years before a type 1 diabetes takes hold - to tackle the immune system dysfunction at the root of the condition. The UK Islet Autoantibody Registry will be critical in seizing this opportunity, helping thousands of families and individuals to get on the front foot of their type 1 diabetes journey. It will enable access to the care they need to prepare for a life with the condition, as well as clinical trials of new treatments that can hold off the immune attack and delay the need for insulin.”

This collaborative initiative will be led by the University of Oxford, co-led by the University of Cambridge and involve researchers from Birmingham, Dundee, Imperial College London, Bristol, Edinburgh, Cardiff, Exeter and the British Heart Foundation.